This is the first post of a four-part series on potentially higher future oil prices and how to exploit that possibility using a three-pronged approach, the Trident Trade. This post will discuss the thesis, address its weak spots and introduce the trade, while the following posts will look at each component of the Trident Trade individually.

The Thesis

To put it simply, I am of the belief that we have entered a period of higher oil prices. I know neither by how much prices are going to rise nor how long they will remain elevated. Per Howard Marks’ rule number one, “most things will prove to be cyclical” and commodities - especially oil - mark no exception. Because nothing cures high prices like high prices, there will inevitably come a point at which enough new production is incentivised to turn the market into surplus, eroding prices. Or we enter another recession that will see demand crater. Or prohibitively high oil prices spark enough investment into renewables, making them reliable enough to reduce demand for oil. Most likely a combination of the above. I do, however, believe that prices will continue to rise before we get there. Or to be more precise, to my mind there is a decent chance oil prices two to three years from now will be higher than they are today. A couple of things have me hold this conviction:

Capex for new developments - esp. from oil majors - has been in decline for a number of years (see Fig 1) and with growing pressures from investors to become ESG-compliant, I do not see this trend reversing easily.

Fig 1: Global O&G Upstream Investment

Both the ESG agenda to have majors favour investments into renewables over fossils (such as activist Engine One at Exxon), as well some of the policies in OECD countries appear for the most part to aim at restricting supply, not demand.

At the same time, global oil demand has recovered nicely from its trough in spring 2020 (see Fig 2) and is on track to eclipse the record demand of 2019 sometime this or early next year per EIA estimates.

Fig 2: Global Oil Demand

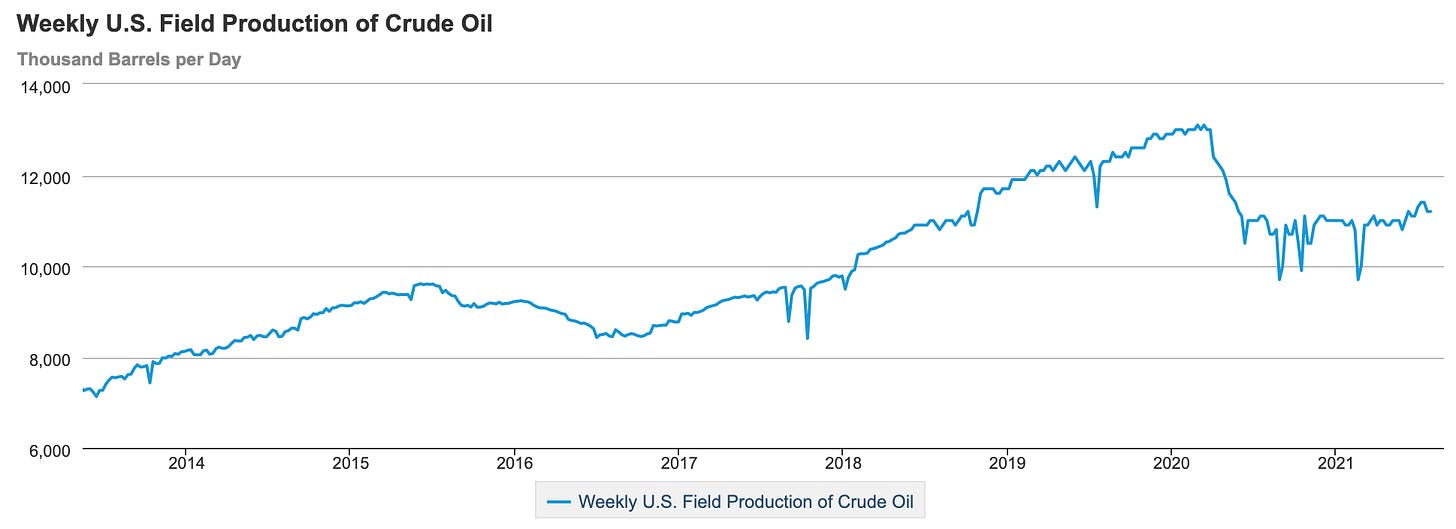

Lastly, recovery in U.S. oil production - or shale in particular - which crashed the party the last two times around, has been anaemic thus far, as evidenced by production (see Fig 3) and rig count (see Fig 4).

Fig 3: U.S. Oil Production

Fig 4: U.S. Oil Rig Count

Addressing the Weak Spots

As I see it, there are four scenarios that could derail my thesis:

Policy measures reducing demand

China slowdown

Return of shale

Opec spare capacity

Policy measures reducing demand

In the U.S., the White House has just announced that President Biden will sign an executive order mandating that by 2030, 50% of new vehicles sold will have to be electric. While this would indeed constitute massive growth for EVs (and deal a blow to gasoline-fired car sales), which currently only comprise about 2% of new vehicle sales, the nine year time horizon of this decree would still allow for my thesis to play out over the next couple of years.

Similar measures and more have been introduced by the EU as part of the European Green Deal with the goal of making the EU largely climate neutral by 2050. Again, I believe the time horizon of this initiative should have a negligible effect on my thesis.

China slowdown

For more than the past decade, the Chinese credit impulse has had a significant inflationary or deflationary impact on a variety of assets across the globe as illustrated in Fig 5.

Fig 5: Chinese Credit Impulse Cross Asset Correlations

In early 2021 the credit impulse peaked (see Fig 6), sparking fears of a deflationary slowdown that would put an end to the reflation trade that appeared so consensus (e.g. UST 2s10s curve steepeners, long cyclicals, long commodities).

Fig 6: Chinese Credit Impulse

Sure enough, many components of the reflation trade peaked at varying points in Q2 2021. But this is not a reflation trade (per se). And slowing growth in China constitutes only one aspect of the demand side of the equation. For the success of this trade, I would put greater emphasis on the supply side. Capital starvation is not exclusive to oil and has already contributed to the massive rallies in other energy commodities and their producers this year (i.e. coal and gas).

Return of shale

Shale oil and gas companies have an illustrious boom and bust history and have often been notoriously poorly managed destroyers of capital. Yet the industry has bounced back multiple times. Or as one HF manager I follow put it, “if an astroid hit the earth, [the] only creatures to survive would be cockroaches and nat gas shales CEOs…”. This has been made possible by repeated recoveries in oil and gas prices as well as investors’ willingness to buy debt issued by these companies on a search for yield due to chronically low interest rates. Sound familiar? Despite talks of a newly-found capital discipline and a focus on shareholder returns among shale executives I would expect production to recover eventually as shale companies do what they always did. Drill, Baby, Drill! It took production about two and a half years to reach its 2015 peak during the last bust and the recovery has been far more muted this time around as demonstrated in Figs 3 and 4. I am confident the thesis will play out before shale production is back in full swing. By keeping a close eye on the data, adjustments can be made should the tides turn.

Opec spare capacity

This is most likely the greatest risk to the trade as well as the most contentious aspect of the thesis. The EIA estimates OPEC spare capacity will average 6.7 million b/d in 2021 and 4.8 million b/d in 2022 (see Fig 7). They add that, “even with increased OPEC crude oil production, remaining surplus production capacity will be more than sufficient to meet additional demand should consumption exceed our expectations”.

Fig 7: OPEC Spare Capacity.

At the same time they admit that, “our OPEC crude oil production forecast is subject to considerable uncertainty”. Furthermore, industry specialists such as Josh Young of Houston-based Bison Interests have expressed doubts regarding the actual spare capacity of OPEC and Russia. Another aspect to keep in mind is that when in 2015 OPEC decided not to reduce output it was to hurt U.S. shale producers that were supposedly operating at much higher breakeven levels in $/b. As it turned out OPEC members did not consider their own fiscal breakeven levels, i.e. what $/b they needed to generate in order to balance their households. With shale production still well below its March 2020 levels, and OPEC only agreeing on moderate supply expansion at their last meetings, I feel confident in my assumption that they want to enjoy the fruits of higher oil prices for the time being. Naturally, this can change at any moment. But this trade would not offer the rewards I think it has without any risks.

The Trade

None of the above constitutes profound insights, nor is it actionable. Let us therefore look at how the trade is looking to capture the thesis:

In the thesis I wrote that to me “there is a decent chance oil prices two to three years from now will be higher than they are today”. Looking at the slope of the WTI futures curve, I can see the market does not agree with me. Spot prices trade at a considerable premium to dates further out the curve, which is referred to as backwardation (see Fig 8). I will express my variant perception through the use of long-dated call options on futures further out the curve. These options have the potential to deliver substantial gains should the thesis materialise.

Fig 8: WTI Oil Futures Curve

Due to the decrease of capital investment in upstream projects from majors, future supply will have to come from different places. One such place could be exploration companies with large, undeveloped deposits. The company I have singled out currently trades at a fraction of the value of their recoverable resources, has no debt, and could be generating cash flow within a year.

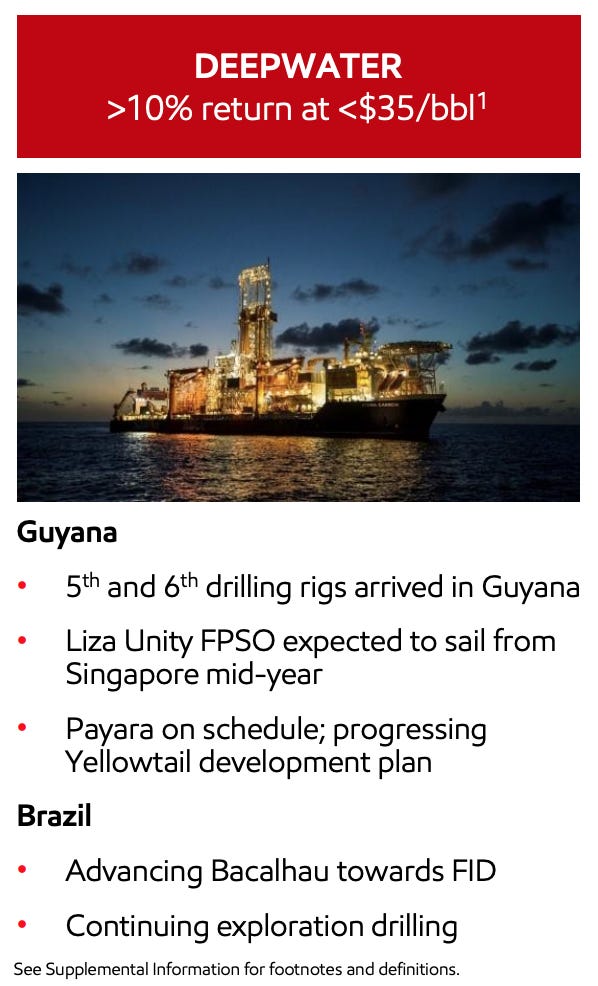

One of the places that I could see majors investing in upstream is offshore. Offshore breakevens have come down a lot and e.g. Exxon claims deepwater to be profitable with oil at $35 already (Fig 9). Furthermore, offshore is considered one of the (relatively speaking) cleaner methods of oil generation. When a major is looking to drill offshore, they contract jackups/rigs from offshore drillers for a certain day rate. Offshore drillers have gone through two restructuring waves with the last six years. Virtually all companies in this sector have either filed for bankruptcy or remain heavily indebted. One of these companies will form the last prong of the trident. With the restructurings, scrapping and consolidation that have already taken place - and offshore as a method profitable for majors at current oil prices - I view this sector as primed for a cycle turn.

A common trait (besides a link to the price of oil) all three prongs of the trident share is the convexity of payoff as well as the non-negligible chance of complete loss of capital. I consider the options the “cleanest” play on the thesis, albeit with the catch that the thesis does not only have to materialise for the options to pay off, it will have to do so prior to the expiry of the options. The exploration play - while less tied to a specific time frame - is somewhat binary in the sense that in order to rerate the deposit must either be developed or bought with the assumption that it is economic for the acquirer to develop. The offshore driller, perhaps least tied to the price of oil once above offshore breakevens for long enough, will have massive torque should that industry recover. On the other hand, given the capital-intensive nature of the business, there is a decent chance it will run out of cash and default within the next two years.

Synopsis: the Trident Trade is looking to exploit the idea of higher oil prices over the coming years by entering into three trades with plenty of optionality (and plenty of risk), each geared to slightly different parameters of the thesis playing out.

Thank you for reading,

LazCap

NOT FINANCIAL ADVICE

The information contained on this Website and the resources available for download through this website is not intended as, and shall not be understood or construed as, financial advice.